“Somewhere along the way I started bleeding”: El Paso, Elsewhere Review

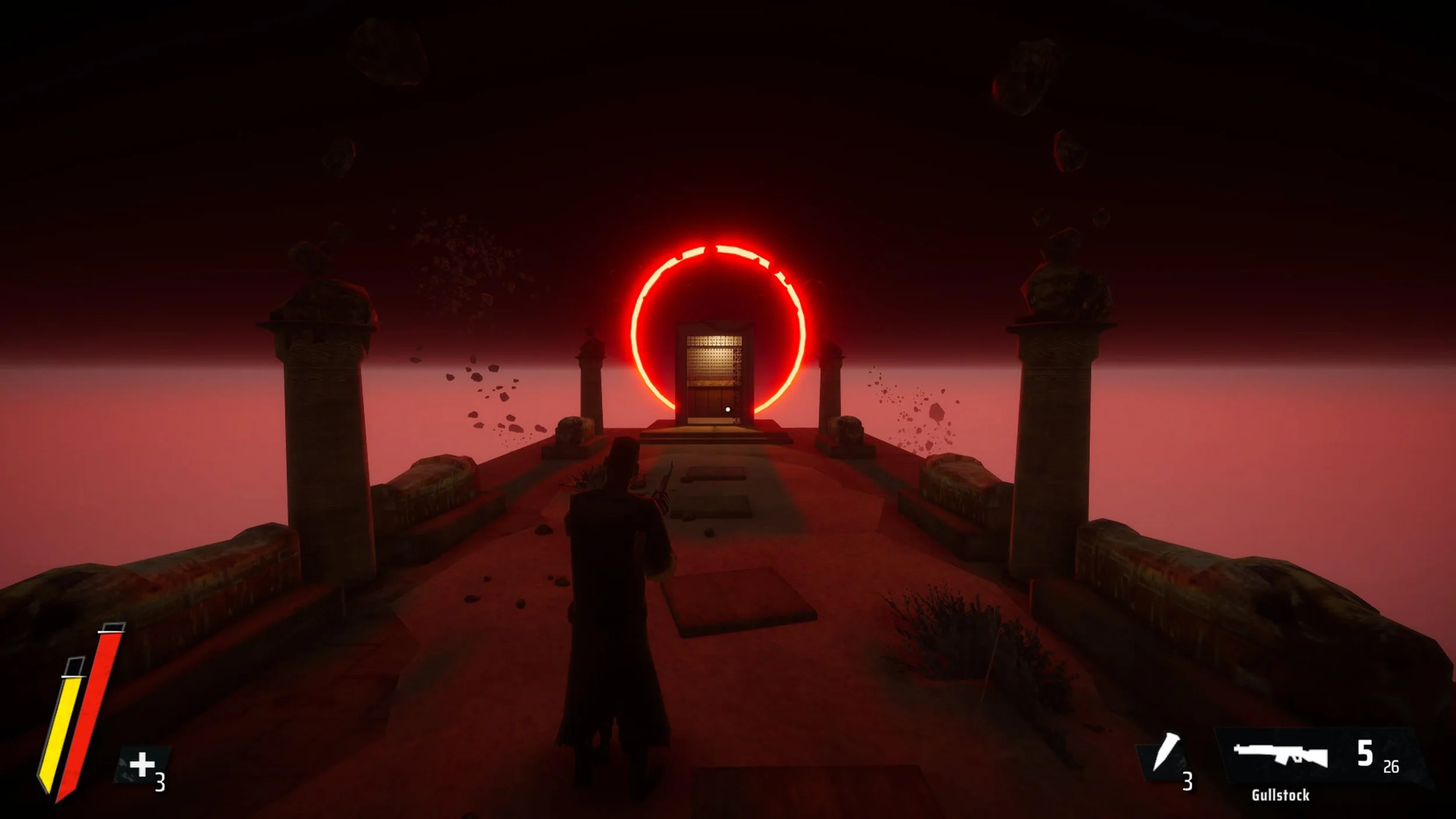

El Paso, Elsewhere by Strange Scaffold. Images by me.

Developed by Strange Scaffold and released in September of last year, everything in El Paso, Elsewhere, from the graphics to the gameplay, is an homage to the Max Payne series (specifically the entries from the early 2000s). It’s a third person shooter with a slow motion mechanic that you’ll use to kick down doors and amass headshots. This shooting is accomplished using an arsenal of shotguns and machine pistols named things like “Calvary” and “Strikebreaker”. A stash of painkillers keep you on your feet and you’ll be administering them as needed–for me, “ as needed” is a synonym for “frequently.” I’d be slamming pills too if I was forced to harvest stakes by rolling into every armoire. It’s a lot of repetition, but as the screen boldly informs you each time you take too many fangs to the throat: you keep going.

In El Paso you play James Savage, a researcher who throws away his six months and 11 days of sobriety to pursue his ex-girlfriend into the abyss below a rural motel. When they were together, he knew her as Janet Drake, but she’s since been promoted to the lord of the vampires and goes by Draculae. She’s performing a ritual and you’re the only one who can kill her and save the world. As James descends, he’ll steadily rescue innocent sacrifices and repeatedly get back on an elevator, a miserable metal box suspended over the underworld, until he reaches the bottom.

The civilians that need saving are marked by beacons of light meant to guide you (ceilings are uncommon in the abyss so these spotlights travel high into the sky). It’s a strange choice but it’s also necessary because getting turned around is inevitable. You’ll be traversing the same hallways, decorated with the same mausoleums, and studded with the same splintered armoires. These are not lived-in places but arenas. Of course, you could make the argument that this applies to ALL video games–levels are little more than fancy rectangles floating in game engines built to hold storytelling. Here, because the set dressing is so bare, it’s more noticeable. The theming gets more interesting the deeper you go, but it never quite shakes that initial standard (and eventually stale) composition. The idea of a favorite level or favorite part is probably not a sentiment you’ll carry as the credits roll. Still, don’t confuse simplicity with mindlessness because you’ll regularly find ways to backpedal into an enemy or get hung out to dry when getting hung up on a rough edge of geometry.

Shambling between James and his objective is an army of mummified nosferatu, bloodstained brides, and biblically accurate angels that fire (probably) biblically accurate harpoons. The bestiary rarely expands beyond this set but is mixed and remixed in a way so that encounters remain intense and interesting for the duration of the runtime. The endless fighting can get old but activating slow motion at just the right moment to unload a shotgun into a leaping werewolf’s chest never does. Usually the amount you can get away with doing something over and over depends on how “cool” said thing is--and El Paso, Elsewhere bleeds cool from every one of its gunshot wounds.

The narrative has some of my favorite writing in recent memory. Observations and introspection are limited to short, punchy sentences with a constant emphasis on futility. It’s a noir and you’ll leave every cutscene with at least one yearbook quote. The relationship between James and Draculae is the beating, bloody, anatomical heart under these digital floorboards and I was consistently seduced by their interactions. One of the collectibles scattered throughout this version of hell are film projectors that play snippets from their past–slices of their life together before things went bad. It’s a surprisingly tragic story for a game that demands you slap a fresh magazine in your Uzi and lay on the trigger every ten seconds.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the “correct” way to enjoy video game music. Theoretically, if you listen to a soundtrack prior to playing the game it was composed for, you’ll lose some of its impact. It’s the genre I listen to the most while working so some contemplation on the subject is inevitable. But does it matter?

Does any of this matter?

Full disclosure, I’ve been banging the El Paso soundtrack since its release. The songs range from upbeat and pulsing (the sort of track that Blade would butcher a slaughterhouse rave to) to lofi from hell. Other songs lean fully into hip-hop. It’s better than anything the best original song category at the Oscars has produced in years. I mean, listen to this and tell me it doesn’t give you that extra kick to face (and fight) the day:

There are a ton of accessibility options and the design dork in me loved that you can see how each default difficulty tweaks each slider. The checkpoints are kind and the only penalty for knocking it down to a lower difficulty setting is restarting the current level. There are a total of 50 stages which should take you around eight hours to complete. I’d recommend short sittings–but with the built-in brevity, I could also see this becoming a “just one more” situation if you find yourself addicted to the loop.

I didn’t encounter any glitches on PlayStation 5. However, I was occasionally confronted with moments of intense slowdown (and not the doves in a church balletic kind). I’m assuming the particle effects are the culprit here because the stuttering was at its worst after tossing a molotov cocktail (which is accompanied by a plume of holy fire) and when sparks started flying as my bullets flattened against the breastplates of the living armor enemies. Ugly, but this choppiness was only an issue during the game’s bosses. They’re already not good, but when the only interesting thing about them is learning the timing of their attacks, that extra chug made defeating them almost impossible. I kept going, of course–but it was the only instance that I wasn’t happy about it.

As much as I could continue to praise Strange Scaffold’s creative choices, if the combat doesn’t click with you, there isn’t going to be much for you here long term. Going through the same architecture for the tenth or twentieth time will feel that much more repetitive if the experience of actually playing it is “just okay.” It’s the rose-tinted glasses you slide on when you meet someone new–but like most relationships, as things quickly become routine, it loses some of its luster. Still, there are worse places you could take a doomed road trip to than El Paso.

At least go listen to the soundtrack.

74/100